The medium of a story certainly does not determine either its content or its quality, but an individual medium offers opportunities and limitations that others don’t. This can create “temptations” to do things that might not be ideal for the story, because it’s easy to do in your chosen medium, or alternatives to doing it are hard in your chosen medium.

Obviously, there’s a lot of subjectivity to this. The comic I’m talking about today, Detective Comics #950 (or, more specifically, its first story), has, in my opinion, fallen into a pitfall that’s more likely to be fallen into by a comic book than other media: the pitfall of embracing verbal explanation (in this case, in the form of narration) so much to the point that it’s too big a part of the story. But the idea that this is a “pitfall” isn’t an objective fact, and I need to clarify that I still enjoyed the story a good deal. I’d probably give it about a 7/10. It was engaging and emotional with excellent artwork. But I do find its narration-focused format questionable and I want to talk about it, and also get into a larger discussion about differences between media.

Check out Brandon Mulholand’s review of this comic on Batman News if you want to read a review that focuses more on the positive aspects of the story and justifies the reliance on narration (and also comments on the other stories in the comic). I will refer to this review a few times in this post to compare and contrast its view with mine, since I think it’s an insightful article.

Now Let’s Talk About The Story

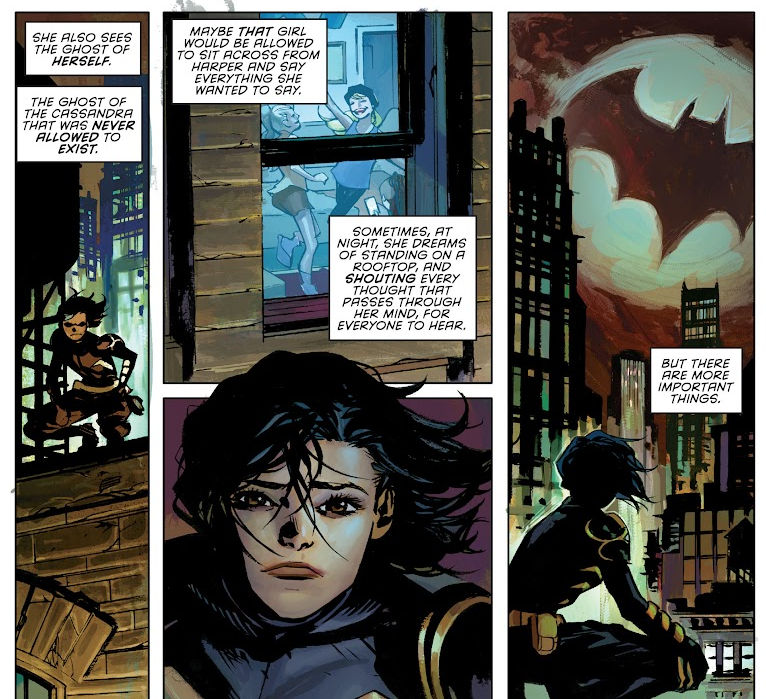

Detective Comics #950’s first story focuses on Cassandra Cain, whose superhero name is Orphan (though she’s also been a Batgirl). Here’s the thing about Cassandra which makes this story’s heavy use of narration both more understandable and more questionable: due to the bizarre way in which she was raised, she can barely speak. It’s not because she has a physical impairment, but because she wasn’t raised with verbal language and that kind of thing is hard to acquire later. She can convey simple messages with a few words at a time, but that’s about it.

This means, on one hand, I get why an author may feel that extensive prose from a third-person narrator is necessary to convey her internal world: she can’t actually talk about it. You can’t even directly say what she’s thinking, because she’s not thinking it in words. On the other hand, it’s quite ironic in a way that creates some distance from who the character actually is. This is a character who can’t even speak a sentence, but her innermost thoughts are being described using many sentences. It’s unfitting.

But let’s look at the positive side of using narration for this: clarity. The text is certainly well-written and evocative. Reading it is still enjoyable, and most of all, there is no ambiguity. We know exactly what she’s thinking. This is one of the main arguments used by Mulholand to support the idea of this use of narration as a positive. He points out that comics lack some of the capabilities of other media, such as movement (which can make facial expressions clearer, among other things) and musical cues, that make it easier to convey emotion. “Prose simply helps to add another element to the story that we can use to interpret what is going on more easily,” he said, and also, “[I] feel like it eliminated a lot of the second guessing that can come from relying on visuals alone.”

This is a fair point, but I think the power of a well-drawn single frame of facial expression is still very significant, and comics also have the ability to use visual flourishes that might not fit in with live action media (though this seems to be something that is taken advantage of more in manga than American comics). That said, I can’t deny the truth: adding text explanations does make things clearer and more straightforward to interpret.

Maybe the deeper question is, is that necessarily a good thing?

Room for Interpretation Can Be a Wonderful Thing

One of the great things about YouTube is that it makes it easy to access clips of content that is not readily made available by modern companies. For example, you can watch clips of the original version of the Star Wars Original Trilogy. I’m not exactly breaking new ground with this take, but many of the “Special Edition” changes made by George Lucas over the years are horrible. They don’t ruin the movies, but they do make them worse. And to me, perhaps the worst change is making Greedo shoot first, unlike the original, where he didn’t even get a shot off before being blasted by Han Solo.

The reason I’m going down this tangent is because, while reading comments on some of the various uploads of this excellent unaltered scene, I was intrigued by how people’s interpretations of it differed slightly. Crucially, the basics of what happened are clear and agreed upon: Han knew Greedo wanted to kill him even though he didn’t get a chance to raise his weapon, so he killed him before that could happen.

But some of the exact specifics, and what exactly this says about Han, has multiple interpretations. Does the scene show Han’s cold-hearted criminal nature, or is just a simple case of self-defense that doesn’t portray any negative qualities? Was he trying to talk Greedo out of his course of action, or just trying to distract him while he readied his gun?

I have my own interpretation which is sort of in-between. The scene shows us Han’s world, a kill-or-be-killed world. This specific action is one of self-defense (though it might not hold up in court), but Han’s choice to live this kind of life is his own, and his total ease and nonchalance shows he’s definitely done this kind of thing before. As to his intentions of what he was hoping to achieve by talking to Greedo, I don’t know. It may have just been a distraction, but I’m not sure.

Honestly, I absolutely love the fact that the basics of the scene are clear and easy to understand, but the exact ramifications of it require some interpretation. It engages the mind to wonder what exactly Han was thinking and to come to your own conclusions. It would not be nearly as good if this was a comic book where Han’s exact thoughts and/or what this says about him was spelled out in thought balloons and/or narration boxes.

When media explains too much and too precisely what is happening, our minds aren’t as engaged, and to me, that often lessens the impact.

How Much Does Medium Actually Influence This, Though?

Of course, over-explaining is not limited to comics, and comics are not always afflicted with it. I’m sure you’ve seen a movie or show with clunky dialogue explaining a plot point in too much detail, and in a way, this is worse, because since it’s conveyed by dialogue, it also requires the character to speak in an unnatural way.

That brings me to my next point: I think certain temptations being stronger in certain media comes from which tools are and are not at that medium’s disposal. I already referred to Mulholand pointing out that comics lack certain tools for conveying concepts, such as motion and music, but I think the temptation also comes from what tools the medium does have. Comics have narration boxes and thought balloons as firmly established conventions, which are the perfect place to put over-explanation. These tools basically allow unlimited internal thoughts and narration to be present in comics.

In media such as shows and movies, it’s very unconventional to contain large amounts of narration and a character’s internal monologue. This forces them to rely more on clunky dialogue, but even less talented writers will probably be able to realize at some point that too much of that is bad and cut down.

Too many narration boxes or thought balloons in comics, on the other hand, isn’t as inherently or obviously bad, so this makes them easy, at least for some writers, to indulge in in large quantities. Detective Comics #950 is the perfect example of this, because the wordy explanatory text is well-written, evocative, and sometimes poetic, so it’s easy to see why James Tynion IV, the writer, saw no need to cut down. I can’t claim his decision was wrong – plenty of people find this story great. Heck, I get a good amount of enjoyment out of it myself.

It’s less that I think it’s a bad story, and more that I see more potential in stories that try to be more balanced. There’s nothing wrong with narration boxes and thought balloons and trying to explain things in prose, but I prefer these elements to be used in a more reserved fashion. A story that leans heavily on narration boxes is a bit frustrating to me, because it basically spells everything out. I want to be able to intuit some things for myself. I want to feel like I’m experiencing the story, not simply being told it.

So, is this article just a long and detailed restatement of the classic “show, don’t tell” rule in storytelling? Well, maybe not quite, or at least, not in the way that rule is usually meant. Because the thing about Detective Comics #950, and most other over-explanatory comics, is that they both show and tell. We still see what’s happening – the environments, the events, the characters’ facial expressions and actions. We just also have a bunch of “telling” to explain to us exactly what it means.

Reflecting on My Own Preferences

Though I cover a variety of topics on this blog, the main focus of the site this blog accompanies is the first two seasons of the 1950s show Adventures of Superman, which is my favorite Superman media. As much as I love comics, I feel like being a live action show (and what kind of show it is) does give Adventures of Superman certain strengths that contribute to my love for it. Part of that is simply that it’s easy for characters to feel real when they’re portrayed by real people, especially when the acting is realistic. And part of that is that not being told exactly what a character is thinking can actually make them seem more interesting. I like just seeing an actor doing a good job portraying a character’s emotions and letting my imagination take it from there.

Even compared to characters in most TV shows (including other versions of Superman), I feel like Superman’s exact thoughts in Adventures of Superman are farther from the viewers because no one in the show knows his secret identity (except temporarily, and his mom, who only appears in the first episode) – he has no confidant, so there’s no one he can speak freely to. Due to this, it is rarer for Clark to say exactly what he’s thinking. However, we can still see his emotions, thanks both to George Reeves’ excellent acting and the camerawork wisely focusing on his face when needed.

I guess I just find this more satisfying than being told directly what a character is thinking. It is ultimately a matter of preference, and there is room in the world both for stories that are very specific about explaining a character’s thoughts and for stories that aren’t. Most stories will probably do best trying to strike a balance between the two. I’m sure for some people, something like Adventures of Superman is too far in the direction of not knowing what the characters are thinking.

It’s hard to conclude this article, since it’s basically just a way for me to reflect on how media tells stories and my preferences regarding this. The subject matter at hand is a complex one that can’t be addressed fully in a short article. Suffice it to say, the best use of verbal explanation stories is definitely a matter of preference. Most stories would probably do well striking a balance, perhaps with a preference towards not explaining too much. For me, connecting with a story can be harder when I feel like I’m being told all the details and meanings instead of being able to draw conclusions based on what’s happening.

Addendum: Additional Comic Examples

OK, yeah, I know the idea of adding an addendum to a blog post seems pretentious. I just feel like this blog post was pretty much long enough, but it would be better if I briefly looked at a couple other comics using over-explanation. I’m not trying to say that most comics or even a certain large percentage of comics have this problem, so I’m not going to give many examples. But giving more than one seems like a good idea.

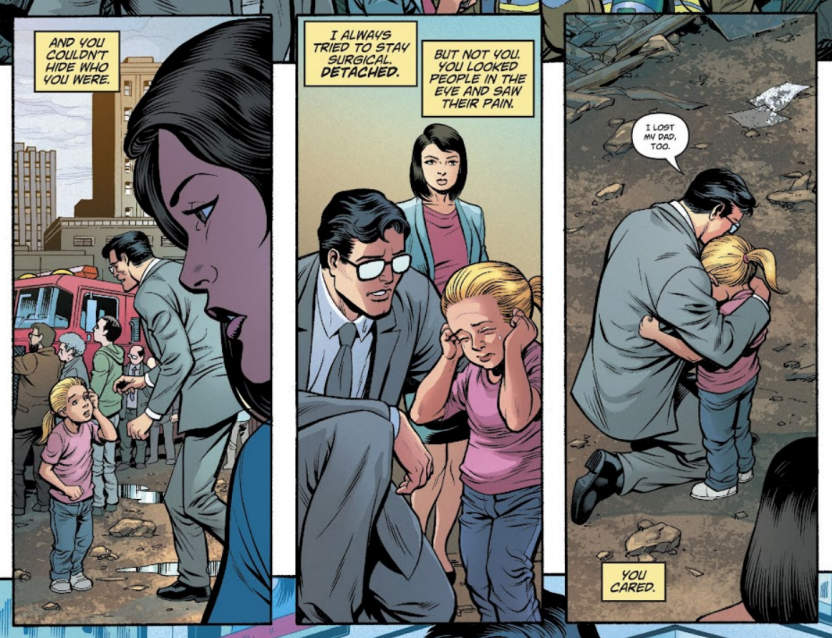

Glasses (from Mysteries in Love & Space #1)

This is a Superman story in an anthology comic, and I enjoy both the story and the comic as a whole. However, it still let me down for a similar reason as the Detective Comics #950, because the story also used a narration box focused format. It’s actually essentially a summary of Lois Lane and Clark Kent’s relationship and to an extent Superman’s adult life in general, with the story shown in the panels mostly consisting of generalized flashbacks. This adds even more distance between the reader and the story because it’s not a story that’s happening in the present.

Still, I think within the confines of the format it’s using, this story works. It has good emotional beats and delivers its message and idea of Superman effectively. Other ways in which the story feels more immediate than the Detective Comics #950 one is that the sentences are a little more straightforward and are also the direct words of Lois Lane.

Overall, it is similar to the Detective Comics #950 story in that it’s good and enjoyable, but I can’t really consider it great because I think its format limits it. It still is mostly based on telling us information as opposed to giving us a story to experience. I respect the story for summarizing Lois and Superman well, but I think a story that didn’t use this much explicit explanation would likely satisfy me more.

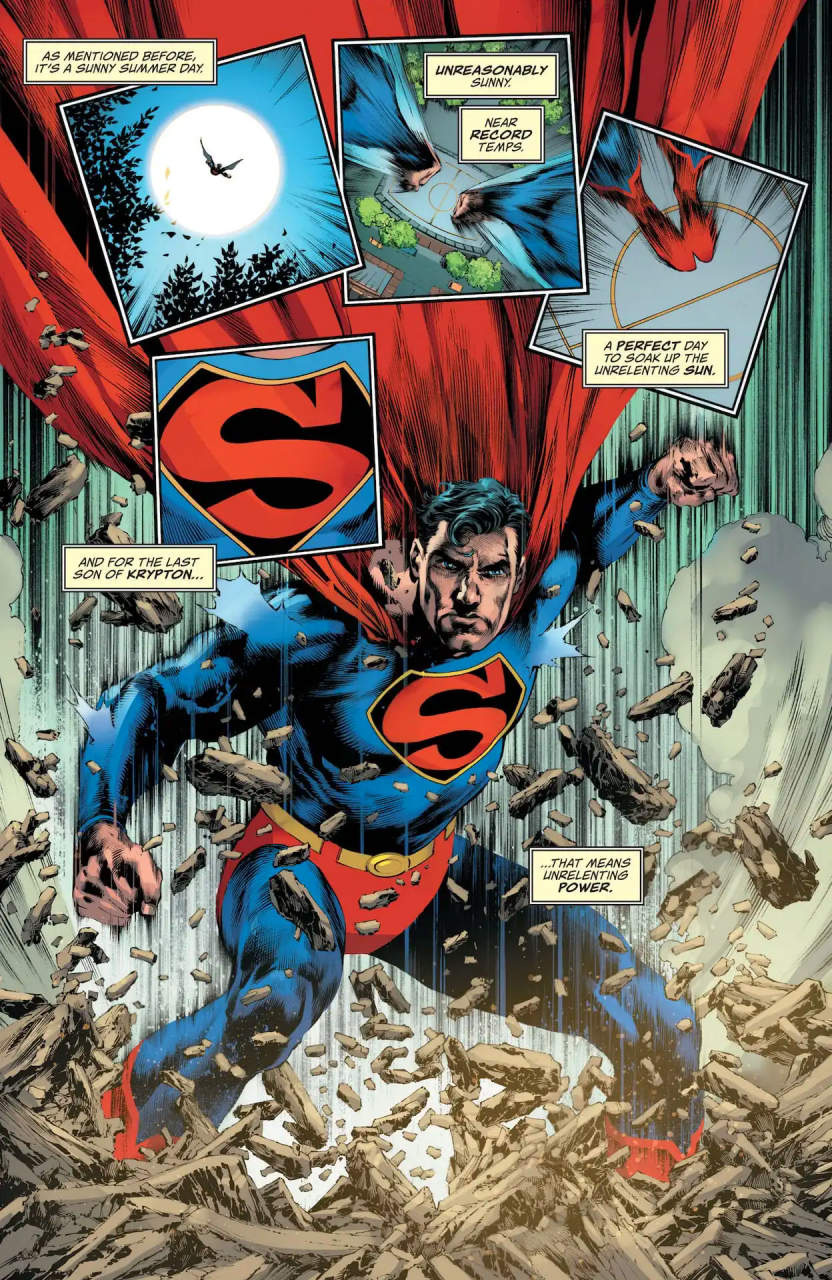

Action Comics #1067 (Main Story)

This is the latest issue of Action Comics and I’m including it as a more minor example. I like the issue quite a bit overall, and unlike the other stories I’ve talked about, it doesn’t use narration boxes as the main driver of its story. They’re just there, alongside the dialog and art.

It also should be noticed that this story has a bit of a “retro” feel, hearkening back to the Bronze Age, and from what I know, that era (and previous ones, to some extent) tended to use more narration boxes and explicit explanation. Honestly, overall, it’s fine. I don’t think the usage of narration is that excessive, and I like some of it. Some of it does add to the scene and add a little depth to what’s going on.

Still, it sometimes feels unnecessary and like it doesn’t really add much. And when that happens, sometimes the narration boxes feel more like a mere distraction, doing little other than adding a slight bit of distance from the proceedings and arguably adding some sort of atmosphere.

I’ll go ahead and give a good example of narration in this story and a bad example (just in my opinion, obviously). I like the following page a lot. Particularly, I love the art, but there is no dialogue. The narration boxes give me an excuse to slow down and savor the artwork and the action it conveys. The very fact that there’s text there makes the scene slower and more dramatic.

And while technically we don’t really need to know the information they convey (at least in this issue, what it talks about doesn’t have any direct impact we can see), it’s still information we can’t get from the images alone. Obviously we can’t tell just by looking how hot it is, and even as a big Superman fan, I wouldn’t have really thought about his powers being boosted by the sunny day.

Overall, the narration on this page adds dramatic effect and atmosphere in a way that I find worthwhile. Plus, it helps us slow down and appreciate what’s happening.

Now for the not so good example, which is actually just slightly before the above good example. It’s not horrible, but it strikes me as almost totally pointless.

We can clearly see everything the narration describes – there’s an explosion of energy and a monster appears. Like the other page, it makes us slow down and could be said to add dramatic effect, but I don’t really think that adds much here. It would probably emphasize how chaotic and sudden this was if we didn’t have to slow down and read this needless explanation of the obvious.

The Conclusion (for Real This Time)

This article was a little rambling, touching on various pieces of media that aren’t directly related to each other. It’s pretty different from most of the other posts on this blog since it deals more with a broad storytelling concept more than just my specific feelings on specific pieces of media. Writing it involved a lot of introspection of what I enjoy in stories and how stories can facilitate that enjoyment. Many of the things I talked about weren’t things I planned on saying when I started it.

All that to say, this post was a bit all over the place, but I enjoyed writing it and I feel like doing so helped me understand why I enjoy the media I do. I certainly hope you got something out of reading it, too!